#GoodReads – Attracting Birds with Native Plants

#GoodReads – “To Bring Birds To Your Garden, Grow Native Plants: Here’s How To Get Started”

#GoodReads – “To Bring Birds To Your Garden, Grow Native Plants: Here’s How To Get Started”

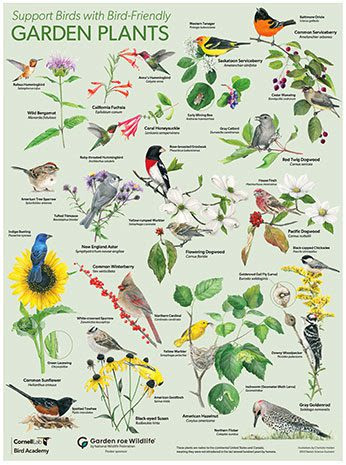

“…One way to get close to birds is to look for the plants that feed them. In spring, Red-eyed Vireos, Yellow Warblers, and hosts of other songbirds nab caterpillars by the dozen off emerging white oak leaves, while Cedar Waxwings and Gray Catbirds seek out sweet purple serviceberries. Summer takes hold and Ruby-throated Hummingbirds sip the nectar of wild bergamot, while Anna’s Hummingbirds gulp from California fuchsia. Come fall, flocks of American and Lesser Goldfinches feed on the seedheads of black-eyed Susans and common sunflowers. Throughout the winter American Robins and Northern Mockingbirds pluck hawthorn and winterberry fruits still dangling from bare branches.

When you see a bird on or around one of these native plants in your yard or neighborhood, it’s more than a coincidence, says Cornell Lab of Ornithology native plant specialist Becca Rodomsky-Bish, project leader for the Great Backyard Bird Count: ‘These are all plants that have grown here for millennia, and they have the positive ecological impact to show for it. If you love supporting birds and seeing them up close, then you can make a huge contribution to them and to yourself by growing these kinds of plants.’

Doug Tallamy—professor of agriculture and natural resources at the University of Delaware, and author of the native-plants-landscaping book Bringing Nature Home—has spent decades documenting the strong connection between native plants and healthy bird populations. In 2009, Tallamy and his team found that yards in southeastern Pennsylvania filled with mostly native plants—including ground cover, shrubs, and trees—hosted four times as many caterpillars (a key food source for breeding birds) as yards with non-native vegetation. In the same study, bird species of regional conservation concern, such as Wood Thrush and Blue-winged Warbler, were found eight times more often on those native-plant–laden properties. That same year, Tallamy and his team published a Lepidoptera Index that ranked nearly 1,400 plants from the mid-Atlantic region in terms of how many caterpillar species they support. Big winners included native oaks, cherries, birches, and willows.

In a 2017 study published in the journal Biological Conservation, ecologist Desiree Narango joined with Tallamy to examine the dietary needs of Carolina Chickadees breeding all around the southeastern U.S. She and her team found that the birds mostly avoided foraging and nesting in yards with a high proportion of non-native plants, even when nest boxes were available. In that study, chickadees raised more fledglings in yards with mostly native plants; in yards with primarily ornamental, non-native plants, many chickadee nests failed because there wasn’t enough for the nestlings to eat.

Native plants ‘help maintain or recreate ecological systems and food webs that have evolved over thousands of years to allow birds and biodiversity to thrive,’ says Rodomsky-Bish of the Cornell Lab. ‘Those insects and their caterpillars are just not going to be there if they don’t have the right kinds of plants.’

Native plants also provide more than caterpillars and insects. They are a direct nutrition source for birds in the form of buds, fruits, and seeds. And many—from the tiniest grasses to the tallest oaks—provide places for birds to build nests and find shelter. Benefits like these mean bird populations can thrive year-round in native-plant-dominated landscapes. A 2023 study published in the journal Ecosphere by Cal State Los Angeles ornithologists Noriko Smallwood and Eric Wood showed that native plants can boost bird populations in the nonbreeding season. Bird richness and abundance—how many species were found, and how many total birds were present—both spiked in winter in Southern California yards that were around 80% native plants…”

To read more, click here.